Intracranial bleeds can occur either spontaneously or from trauma, and the clinical presentation will largely depend on the location of the bleed.

These bleeds can happen intraparenchymal (inside the brain tissue) or extra-parenchymal. Classically, extraparenchymal bleeds are categorized according to their anatomical location with respect to the meningeal layers (e.g., epidural, subdural, subarachnoid).

Imaging plays a crucial role not only in localizing the hemorrhage but also in estimating its age, as the appearance of hematomas evolves over time. Regardless of the cause, most intracranial hemorrhages present acutely with neurological symptoms such as headache, vomiting, and altered consciousness.

In emergency settings, a non-contrast CT scan is usually the first imaging test performed. It’s faster than MRI and very effective at detecting acute intracranial hemorrhage, which typically appears hyperdense (bright) on the scan. In cases of head trauma, CT is also more effective than MRI at identifying skull fractures, making it the preferred initial imaging choice.

Epidural Hemorrhage

Epidural hematomas most commonly occur in cases of violent trauma to the temporoparietal regions under which lies the middle meningeal artery. However, in children, the bleed can come from the dural venous sinus.

Due to how dural is attached to the skull, blood from the middle meningeal artery builds up quickly and is unable to redistribute, resulting in a rapid increase in intracranial pressure that is life-threatening.

Epidural hematomas are generally unilateral and have a classic “biconvex” appearance. Given the acuity of the presentation, imaging is usually done with CT rather than MRI.

Subdural Hemorrhage

Subdural hematomas occur from the tearing or breakage of the bridging veins connecting the brain to the dura mater.

They often occur from trauma (generally lower velocity/impact traumas than epidurals) but can sometimes also occur spontaneously in elderly people.

Subdural hematomas have a classic "crescent" shape that does not cross the midline, as they are confined between the falx cerebri (dura mater) and the arachnoid.

However, if a subdural hematoma is large enough, it can push on the rest of brain, causing what is known as a midline shift.

This presentation is usually accompanied by signs of increased intracranial pressure.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Subarachnoid hemorrhages can occur in traumas, but can also happen spontaneously from the bursting of an intracranial aneurysm. The appearance of a subarachnoid hemorrhage can be more subtle and differs based on the location and size of the burst artery. Generally, these types of bleeds can cross the midline and often appear to outline the folds of the cortex.

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

An intraparenchymal hemorrhage is often used synonymously to describe a hemorrhagic stroke. This is a kind of bleed that occurs within the brain tissue itself and presents with focal neurological deficits, similar to an ischemic stroke.

Non traumatic causes include hypertensive bleeding, amyloid, arteriovenous malformations, tumor, etc. Intraparencymal bleeds vary greatly in terms of appearance and location- they are generally irregularly shaped and are often accompanied by effacement of normal brain structures in the areas surrounding the hemorrhage.

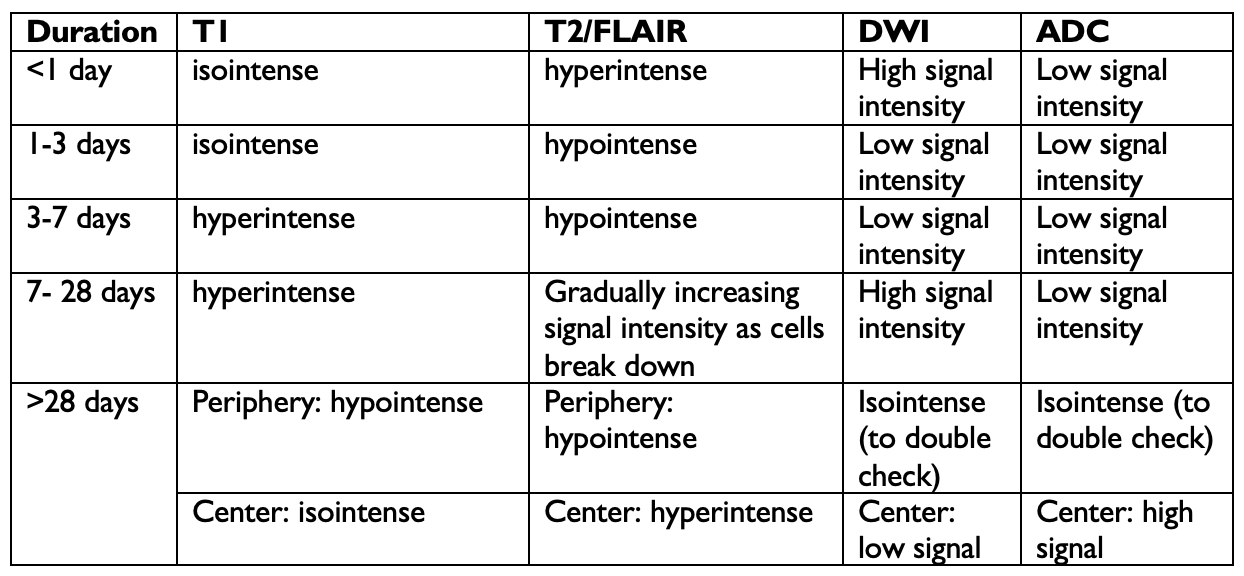

Hematoma Appearances Based on Age of Bleed

On MRI, acute bleeds (<12 hours) will appear isointense on T1 (indistinguishable from adjacent parenchyma), hyperintense on T2 and attenuated on FLAIR.

In bleeds that are 1-3 days old, the main content is deoxyhemoglobin, which will appear isointense on T1 (indistinguishable from adjacent parenchyma) and hypointense on T2 and FLAIR, which will start from the outer margin of the hematoma.

By days 3-7, the hematoma will begin to appear hyperintense on T1 while remaining hypointense on T2 and FLAIR.

After 7 days, the hematoma will be hyperintense on T1, T2 and FLAIR.

Eventually, after a few weeks, hemosiderin and ferritin deposits form in the location of the bleed and remain for many years. These appear hypointense on T1, T2, FLAIR and T2* sequences.

Summary Table:

*This is a simplified representation. In reality, hematomas often have heterogenous appearances which reflect the different ages of the blood within a hematoma that is transitioning between acute, subacute and chronic phases.

Clinical Nugget: The most important risk factor for a spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage is hypertension . Hypertensive bleeds occur most often in deep brain areas, such as the basal ganglia and the thalamus (lacunar bleed), but can also happen on the pons, the dentate nuclei and the cerebral hemispheres. Other common causes of spontaneous intracranial bleeds are ruptured aneurysms, vascular malformations, vasculitis, venous or venous sinus thrombosis, tumors and anticoagulation . In the last case, the hemorrhage can occur in very complex and unpredictable patterns.